Heavily pregnant, Miriam, rests on the bed at Am Timan hospital's maternity ward in Chad. A gynaecologist performs an ultrasound examination on her growing belly.

She seems surprised when unexpectedly, on the monitor, the outline of a baby appears.

Her expression quickly turns to relief. The translator confirms that Miriam’s unborn child is progressing well.

Miriam is one of 44 patients with hepatitis E who have been hospitalised in Am Timan since September. More than 320 other potential cases have been identified.

She is from a nomadic community about eight kilometres from Ardo, a town that’s a three hour drive from Am Timan.

A mother of nine, her tenth child is due in February.

"I felt so sick" - Infection during pregancy

Miriam was brought to Am Timan after seeking treatment at a Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) mobile clinic in Ardo.

“I was not able to feel the heartbeat of the baby for over a week," says Miriam. "I spent 25 days in my bed without moving.

"It was the first time I felt so sick”.

The team immediately recognised the symptoms of hepatitis E, including jaundice, and decided Miriam needed further treatment at the hospital.

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is the yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes. It’s one of the most obvious signs that a person may have hepatitis E.

Veronica Siebenkotten-Branca, an MSF gynaecologist in Am Timan, says hepatitis E has no cure and is particularly dangerous for pregnant women like Miriam.

“Depending on how severe is the hepatitis E infection during pregnancy," she says. "It could lead to potentially serious consequences for maternal and foetal health.

"Abortion, post-partum haemorrhage, a premature baby or still born are among the worst situations a mother can face.”

Within days of her admission to hospital, Miriam’s health had improved.

“Now I can finally feel my baby again," she says. "Before I was so afraid to come to a hospital, but now I feel much better and I hope I will able to go back to my community soon.”

Nomadic life

As she recovers, her husband and three brothers wait outside the maternity ward, worried for her health.

It is the first time she has ever been in a hospital. As a nomad, Miriam and her family rarely spend longer than a few months in one place.

It is estimated that one in 25 patients with hepatitis E is at risk of death. But for pregnant women in their third trimester, the risks of maternal and foetal mortality are higher.

The group moves throughout the dry season to the far south of the country, and then in the rainy season; to the north.

The journey in between can last for over a month, with around 200 people on the move with their livestock, stopping to grow grains along the way.

Hepatitis E and pregnancy

The first cases of hepatitis E were discovered in late August in Am Timan Hospital, where we provide HIV and tuberculosis (TB) care. We also support the paediatric and maternity departments.

Like cholera, hepatitis E is transmitted from one person to another, mainly through contaminated drinking water. The disease rapidly spreads in places where hygiene and sanitary conditions are poor.

It is estimated that one in 25 patients with hepatitis E is at risk of death. But for pregnant women in their third trimester, the risks of maternal and fetal mortality are higher.

Among the nine patients who have died in the past few months, three were pregnant women with jaundice.

Our response: community and hygiene

Since the first hepatitis E cases were identified, more than 600 MSF staff have been working to test for new cases, treat patients and improve the supply of water and sanitation.

Many of those involved are Community Health Workers. Their main role is to talk to people about the early signs and symptoms of hepatitis E and to share information about hygiene practices.

In many cases, hepatitis E patients have been seen as a threat to the community, leading to both stigmatisation and shame for those who are diagnosed.

This work includes meeting with local chiefs, leaders and officials, to hear their concerns, identify needs and encourage them to talk to their community about the urgency of the hepatitis E response.

In the last three weeks, they have also distributed over 11,000 hygiene kits containing bars of soap and buckets.

"Sick people with yellow eyes"

Most people in Am Timan had not previously heard of hepatitis E, and as a result, staff are working to address fear and suspicion about the ‘sick people with yellow eyes’.

In many cases, hepatitis E patients have been seen as a threat to the community, leading to both stigmatisation and shame for those who are diagnosed.

But with support from Community Outreach Workers, this is changing.

patient story: ngomdimadje, hepatitis e patient

Ngomdimadje, a 25-year-old teacher, was the first patient to survive hepatitis E in Am Timan. He lives with his cousins in a rented house in the central Salamat district.

Around four months ago, after he returned from teaching young elementary students, he started to experience severe pain in his body.

At that time, he said he was feeling close to death: with loss of appetite, severe vomiting, headaches and abdominal pains.

He was barely able to move or to walk.

Critically ill, Ngomdimadje managed to travel to Am Timan Hospital where he was told he had hepatitis E.

After being admitted to hospital, his health started to deteriorate and our medical team closely monitored and treated him for over two weeks.

He has now made a full recovery.

“Today, I call myself a survivor," he says. "As long as I am breathing, I survived this potentially deadly disease.

"Before me, the other two patients didn’t make it. Calling myself a survivor is truthful and it is hopeful."

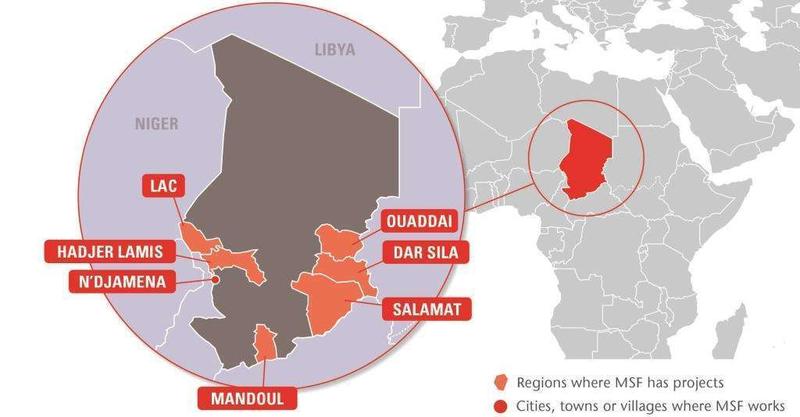

MSF in Chad

We has been working in Chad since 1981. Before the current hepatitis E outbreak, we had been running regular medical programmes in Am Timan and in Moissala.

Earlier this year, we launched an emergency nutrition response in Bokoro. Here, in partnership with the Ministry of Health, we run 15 mobile outpatient clinics and an intensive therapeutic feeding centre in Bokoro hospital to treat malnourished children.

We also launched an emergency response in March 2015 in the Lake Chad region, for people displaced due to violence by Boko Haram.

Teams based in Baga Sola and Bol continue to provide assistance to the population around Lake Chad.

In the capital, N’djamena, we support Ministry of Health hospitals, training staff on the management of mass casualties in order to increase their capacity to respond to emergency situations.