Last year has been the deadliest on record for people making the perilous journey across the Mediterranean.

This article provides an overview of MSF’s figures and a brief analysis on aspects such as the poorer quality of the boats seen this year, the new and deadly tactics of smugglers, the large number of unaccompanied children that have been rescued and the conclusions drawn from the testimonies gathered of the nightmarish transit through Libya.

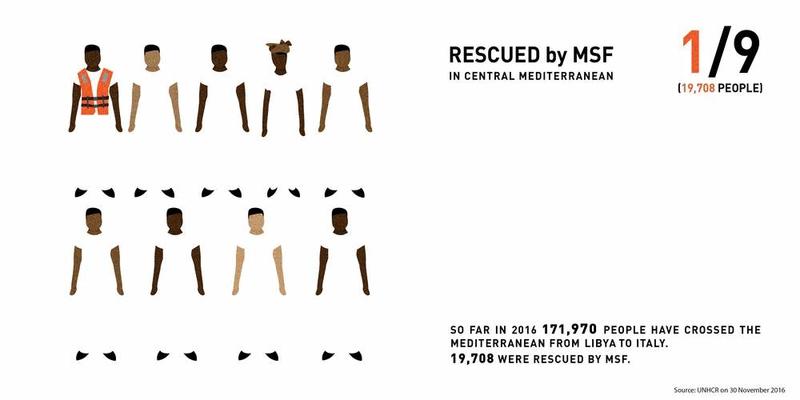

In 2016, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) had teams on board three boats, the Dignity I, Bourbon Argos and the MV Aquarius (run in partnership with SOS MEDITERRANEE). From the beginning of operations in April until 29 November, these three teams directly rescued 19,708 people from overcrowded boats and assisted a further 7,117 people with safe transfer to Italy and medical care. At least one in seven of those rescued on the Mediterranean were helped by Médecins Sans Frontières teams.

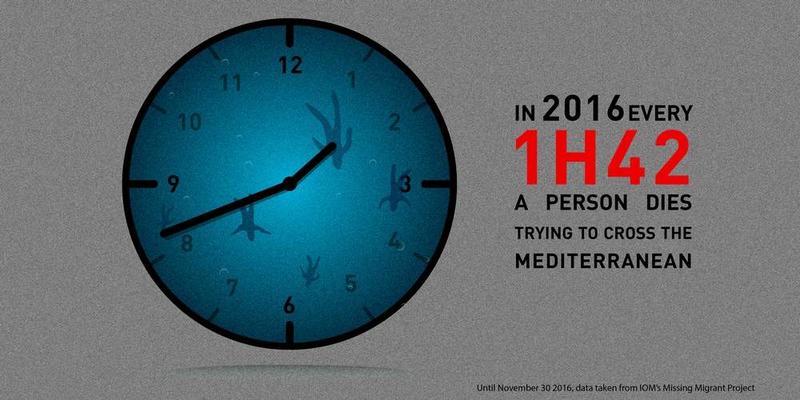

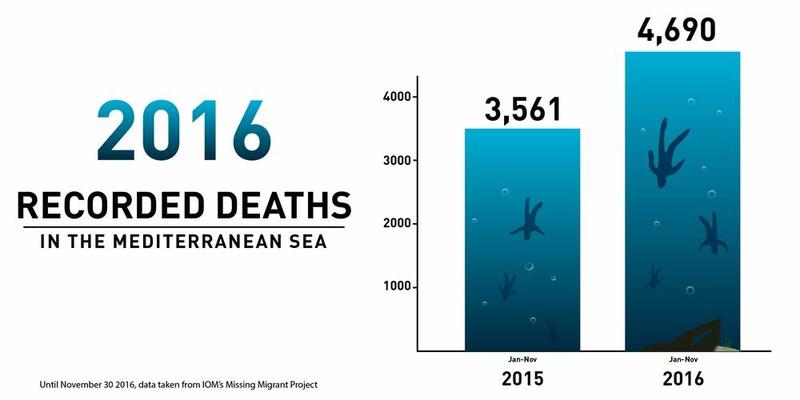

1) 2016 is already the deadliest year on record

Since 1 January, at least 4,690 men, women and children have died while attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea. That’s nearly 1,000 more than in all of 2015 and still with some weeks left to go. This is not due to a significant increase in overall arrivals but, instead, an increase in mortality in the deadly stretch of water between Libya and Italy. In 2016, around 1 in 41 people who attempted to flee Libya by boat died trying.

Despite the shocking figures and the immense loss of life, the European response in the Central Mediterranean has been to declare “war on smugglers” and focus on deterrence measures and the externalisation of borders, rather than on saving lives and enabling a safe passage into the EU. This has served only to force smugglers to adapt their tactics and operate in an even more dangerous way in order to avoid border controls.

2) Men, women and children are being packed into even poorer quality boats

In 2016, MSF teams rescued people from 134 rubber boats of extremely poor quality, and 19 wooden boats. Our teams also recovered the bodies of those for whom rescue came too late. The large wooden boats of 2014 and 2015 are all but gone and have been replaced by cheap, single-use inflatables that the smugglers assume will be intercepted at some point by the search and destroy operations launched by the international military in the high seas.

These shockingly low quality boats have led to tragedy after tragedy, with MSF teams recovering the bodies of people who have asphyxiated – crushed by the weight of hundreds of others in the dinghy – and people who drowned in the bottom of a boat in a toxic mix of sea water and gasoline.

3) Smugglers are more ruthless than ever

MSF teams have seen boats capsize after spending hours or even days floating aimlessly without a motor after it was snatched by smugglers or other criminals well before rescue was possible. Those we rescued have told us told us they were kept in caves, ditches or holes in the ground for days or even weeks before being forced on a boat and sent out to sea. We’ve heard stories of executions, horrific ill-treatment and sexual abuse which, in some cases, amounted to torture. In contrast to last year, we have seen fewer people equipped with life jackets, food, water and other supplies for the journey or even with a sufficient amount of fuel.

We’ve seen rescues come in waves and at all hours of the day and night. Smugglers are sending people out in large flotillas at odd hours in the hope that they will escape the mechanism of control, dissuasion and interception imposed by restrictive policies or that, even if some are captured, the majority will get through and be rescued. Precarious night rescues have become more frequent, as have days where a single rescue vessel has had to respond more than 10 distress calls in a 24-hour period.

4) Large numbers of unaccompanied kids are braving the sea alone

Sixteen percent of arrivals to Italy are children, 88% of whom are unaccompanied. One tiny family rescued by the Aquarius was headed by a 10-year-old boy travelling alone with his siblings, all of whom were young enough to still be in nappies.

5) Many women we rescue are pregnant; many of the pregnancies are a result of rape

Some of the babies are very much wanted and come simply at a difficult time, while many others are the result of rape in Libya, on the road, or in the countries of origin. Many women we rescue, especially those travelling alone, recount horrific stories of rape and sexual abuse in Libya. Many others are too traumatised and terrified to disclose what they have been through to our staff in the short amount of time we spend with them on board.

The threat of rape is so well known, in fact, that some women opt to have long-term contraceptive implants put in their arm before they travel to ensure they do not become pregnant. In 2016, four babies were born on MSF’s rescue boats. It is miraculous that they were rescued in time and by boats with skilled midwives on board. It is genuinely awful to think what would have happened if their labour had started earlier or if they had been rescued by merchant ships without proper medics.

6) MSF is not assisting people smugglers nor are we smugglers ourselves

Let’s make this point clear: MSF are not people smugglers, nor are we an anti-smuggling operation. We're in the Mediterranean to save lives, pure and simple.

Smugglers are exploiting some of the most vulnerable people in the world for profit and their business model exists, in part, due to the lack of any safe and legal alternatives for people to be able to reach Europe. The instability and economic crisis in Libya is also a major factor in the proliferation of smuggling networks.

7) It’s not only women and children who are vulnerable

Each and every person we rescue has a story of hardship and, while women and children have very specific vulnerabilities that need special care and attention, men too have weaknesses that are often more difficult to see.

Some flee wars they want no part in, others torture, forced conscription and mass human rights violations. Others face discrimination based on their sexuality, violence, persecution, extreme poverty and destitution.

Their journey of suffering begins in countries ravaged by years of tension and instability – ranging from as far as Pakistan, to countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Nigeria or Gambia, from the horn of Africa, especially Eritrea, as well as the Middle East.

8) Europe is far from the top destination for the world’s refugees and other migrants

The vast majority of refugees and other migrants have sought refuge or employment in their own region. According to UNHCR data, none of the top hosting countries for refugees – Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon, Iran, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo and Chad – are in Europe but, combined, they provide refuge for more than half of the world’s refugees. Europe has only received a tiny percentage of the world’s refugees but continues to focus on creative ways to keep refugees and migrants away rather than on taking in those in need.

9) Refugees and migrants endure horrific violence and abuse in Libya

No matter their reasons for being in Libya in the first place, the violence and mistreatment refugees and migrants suffer there mean they simply have to get out. According to the people interviewed by our teams, men, women and, increasingly, unaccompanied children (some as young as eight years old) living or transiting through Libya are suffering abuse at the hands of smugglers, armed groups and private individuals who exploit the desperation of those fleeing conflict, persecution or poverty.

The abuses reported include being subjected to violence (including sexual violence), kidnapping, arbitrary detention in inhumane conditions, torture and other forms of ill-treatment, financial exploitation and forced labour.

10) Intercepting boats leaving Libya is not a solution

Preventing people from leaving Libya condemns them to further ill-treatment and physical, sexual, financial and psychological abuse at the hands of smugglers. According to the training plan initiated by the European Union, the Libyan Coast Guard is expected to play a key role in future policies of containment within Libyan territory – carrying out interception, search, rescue and return operations in Libyan waters.

Our experience shows that intercepting overcrowded and unseaworthy boats can be extremely dangerous in this context and can exacerbate the risks faced by those desperate to reach a place of safety. Those fleeing Libya must be rescued in a safe and calm manner and brought to a port of safety where they can receive assistance and claim asylum and other forms of protection. The current situation in Libya means it cannot be considered a safe port of disembarkation.

Find out more about our search and rescue operations on the Mediterranean Sea.