On the eve of the high-level Global Vaccines Summit hosted by Ban Ki-Moon, Bill Gates and General Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, international medical humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) warned that high prices for new vaccines could put developing countries in the precarious situation of not being able to afford to fully vaccinate their children in the future.

“Urgent action is needed to address the skyrocketing price to vaccinate a child, which has risen by 2,700 percent over the last decade,” said Dr. Manica Balasegaram, Executive Director of MSF’s Access Campaign. “Countries where we work will lose their donor support to pay for vaccines soon, and will have to decide which killer diseases they can and can’t afford to protect their children against.”

'Decade of Vaccines'

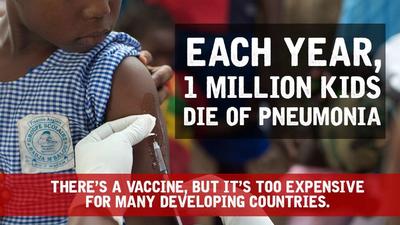

MSF staff preparing the pentavalent vaccine in the Democratic Republic of Congo

© Ben Milpas

The ‘Decade of Vaccines,’ the global vaccination initiative for the next ten years, is estimated to cost US$57 billion, with more than half going to pay for the vaccines themselves. In 2001, it cost $1.37 to fully vaccinate a child against six diseases. While 11 vaccines are included in today’s vaccines package, the total price has risen to $38.80, largely because two expensive new vaccines – against pneumococcal disease and rotavirus – have been added, which make up three-quarters of that cost.

They are only produced by Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), and Merck. Newer vaccines are significantly more expensive: vaccinating a child against measles costs $0.25, while protecting a child against pneumococcal diseases costs, at best, $21.

MSF vaccinates millions of people each year and fully supports the introduction of new vaccines in developing countries. But negotiations between companies and the largely taxpayer-funded GAVI Alliance for the newest vaccines have not resulted in deeper price cuts that would help more children benefit. The lack of transparency by companies on vaccine manufacturing costs and their focus on profits above ensuring sustainable prices for vaccines for low-income countries are at the root of the problem.

More children vaccinated

GAVI has recently announced a new deal to reduce the price of pentavalent vaccine. This is an excellent example of what GAVI can achieve, especially when there are multiple vaccine manufacturers in a market and healthy competition. GAVI should urgently prioritise further negotiations for the two newest and most expensive vaccines and pharmaceutical companies should come to the table to offer GAVI better deals.

“When you start from over-inflated prices charged in rich countries, even getting 90 percent off means paying a price that is much too high for poor countries to afford long term,” said Kate Elder, Vaccines Policy Advisor at MSF’s Access Campaign. “The goal here is to get more children vaccinated with taxpayers’ money. To do that, we need to see prices much closer to the cost of production. GAVI should do more to speed up the entrance of manufacturers with lower costs, so that real competition can lower prices. This is particularly important for the newest vaccines which are unreasonably expensive.”

MSF is also troubled by the fact that non-governmental organisations and humanitarian actors are excluded from accessing the GAVI-negotiated price discounts. MSF is often in a position to vaccinate vulnerable groups, such as refugee children, HIV-positive children and older unvaccinated children who fall outside of the typical age range for standard vaccination programmes.

However, MSF has not been able to systematically access the lowest prices negotiated by GAVI, having to resort to lengthy negotiations with Pfizer and GSK over the last four years to access the pneumococcal vaccine. While the companies have offered MSF donations, this is not a sustainable, long-term solution for MSF as we work to respond quickly to needs in the field, and wish to expand vaccination of vulnerable groups in an increasing number of countries.

“We’re asking GAVI to open up their discounted vaccine pricing to humanitarian actors that are often best placed to respond to vaccinating people in crisis,” said Dr. Balasegaram.