The mental health of patients, their families and frontline health staff has been a fundamental part of COVID-19-related projects run by Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) across the world. For Yotibel Moreno, MSF communications officer in Venezuela, managing the pain caused by the virus became personal when Yotibel’s own uncle was admitted to MSF’s COVID-19 care unit in Caracas.

“COVID-19 causes anxiety among health staff, fear and anxiety among patients’ relatives, and fear, pain and sometimes death among patients.

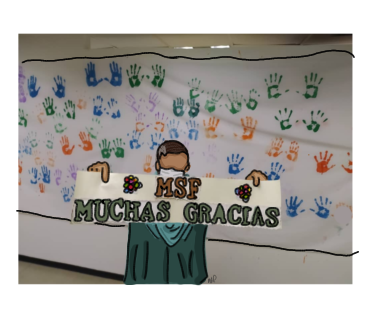

I have worked for MSF since early 2019 and have seen close up the work of doctors and nurses, as well as hygiene, logistics, social work and mental health teams, as they care for patients with COVID-19. I have seen how each element of the system functions, thanks to the dedication of every team member. I have interviewed patients who have recovered and are thankful to the teams for the care they received, and I have cried with emotion at seeing them add their handprints to the hospital wall as a symbol of triumph when they are discharged.

I have also known of patients dying, and have seen how aspects of this pandemic complicate people's reactions to bereavement – including the impossibility of physical contact, the impossibility of closely following the course of the disease, of accompanying a patient through times of discomfort, insomnia, complications or fear, and the impossibility of carrying out the rituals of bereavement and letting go.

MSF has found ways to get around these difficulties. The MSF team cares for patients with COVID-19 using daily follow-up visits, telephone calls and audio and video messages, while keeping relatives informed about a patient's progress or the possibility of a poor outcome. This practice maintains links between patients, staff and family members, helping patients feel informed and helping to manage the guilt sometimes felt by family members for having left loved ones alone in hospital.

This time it was my turn to experience the pain at first hand. My uncle Miguel was admitted with severe symptoms to MSF’s COVID-19 care unit. From the first day, the team called to report on his progress. They talked clearly, giving us all the information we needed. Knowledge brings peace of mind and reduces fear, anxiety and pain. On several occasions, we sent audio messages with encouraging words for Miguel, which kept the family connected to him. The mental health team told us when they had been with him and encouraged us to keep sending audio messages to give him strength. They also monitored our family's mental health by checking in with everyone who lived with him.

The days passed and Miguel's condition worsened. He was admitted to intensive care and one day they gave us the news that no one wanted to hear: Miguel had died.

After the news of his death, time began to pass in slow motion. Fear took its toll; the physical distance separating the family, the impossibility of meeting, hugging and getting through this time, all made it harder. In the middle of a pandemic, knowing that a relative has died, not being able to be with them, being unsure of the steps to follow, makes you sink into a deep state of bewilderment. As at the beginning, the information we received continued to be the best support.

MSF’s mental health team supports families during the process of caring for patients with COVID-19 and prepares them for their possible deaths. When a patient dies, the World Health Organization recommends that relatives be allowed to view the body, without touching it and while maintaining

their distance and taking all necessary precautions to prevent infection. At Hospital Vargas de Caracas, MSF’s mental health team have set up a space for relatives to say their final farewells after a patient has died, while maintaining biosafety measures. In an area separated by a glass wall and supported by MSF mental health staff, relatives can say farewell in an intimate and respectful space.

Some weeks before my uncle’s death, I and a photographer had attempted to document this space and the protocols following a patient’s death from COVID-19. I was aware of the delicate nature of the situation and had no intention of invading the intimacy of this moment for a photo or story. We ended up not taking any photographs as there was no opportunity. I was grateful to the staff for doing their work and respecting the decision of family members not to be photographed. At the end of our visit, the photographer asked me to go behind the glass screen where the relatives sit and took a photo of me instead. In my heart, I was grateful not to have achieved our aim, without even imagining what I would experience days later.

On the morning after Miguel died, I was with my father, my cousin Miguel Angel and his girlfriend, seated opposite the MSF mental health team. With their hands freshly washed and their masks full of tears, the team told us what his final moments were like and what the medical and nursing team had done to help, and they gave us encouragement and listened to us. They told us about the emotional processes through which the family would pass, the psychological support available, the legal steps necessary, and offered us the chance to say farewell.

Denial is the first stage of bereavement; it means not believing it when you receive news of a death. The second stage is anger, anger and frustration; you blame the healthcare system, the doctors or God. Negotiation is the third stage. This is when the process of acceptance begins, although the attempt not to accept it persists; it tends to be expressed in a request for extra time, in the desire for an opportunity to do things better, to rectify things. In this stage, rituals can help you process your loss: scattering the deceased’s ashes in a significant place; preparing a meal of their favourite foods as a tribute; attending mass or any religious practice; or doing any other activity in line with one's values and beliefs.

The fourth stage of bereavement is sadness. Nostalgia wells up; you feel that life no longer makes sense and you feel how difficult it will be to live without this person. You feel, live and acknowledge the loss. The fifth stage is acceptance, when you recognise the loss as a reality.

I returned to the space for final farewells hand in hand with my father, walking where the relatives go, without a camera, without the aim of taking a good photo or getting a good story. This time I was part of the story. I couldn't stop thinking about that time when I didn't achieve my aim, and at that moment I understood that no, this is no time for photos. The dignity of that moment and the privacy of the pain deserve only words.

We entered, we said goodbye. With great sadness about Miguel’s death, I would like to thank each of my MSF colleagues for the respectful, humane and professional treatment they offer each patient with COVID-19 and each suffering family member. I would like to tell the rest of my family that we came, we said farewell, no loose ends were left, and we were finally able to close the cycle of pain.