Uprooted Rohingyas Hasina, Fatima and Mohamed now live in Bangladesh. They don’t know each other, but they share the same fate as the hundreds and thousands of other Rohingyas forced to flee Myanmar last year. They have something else in common as all three of them live with their families in Camp 18. Here’s what they have to say.

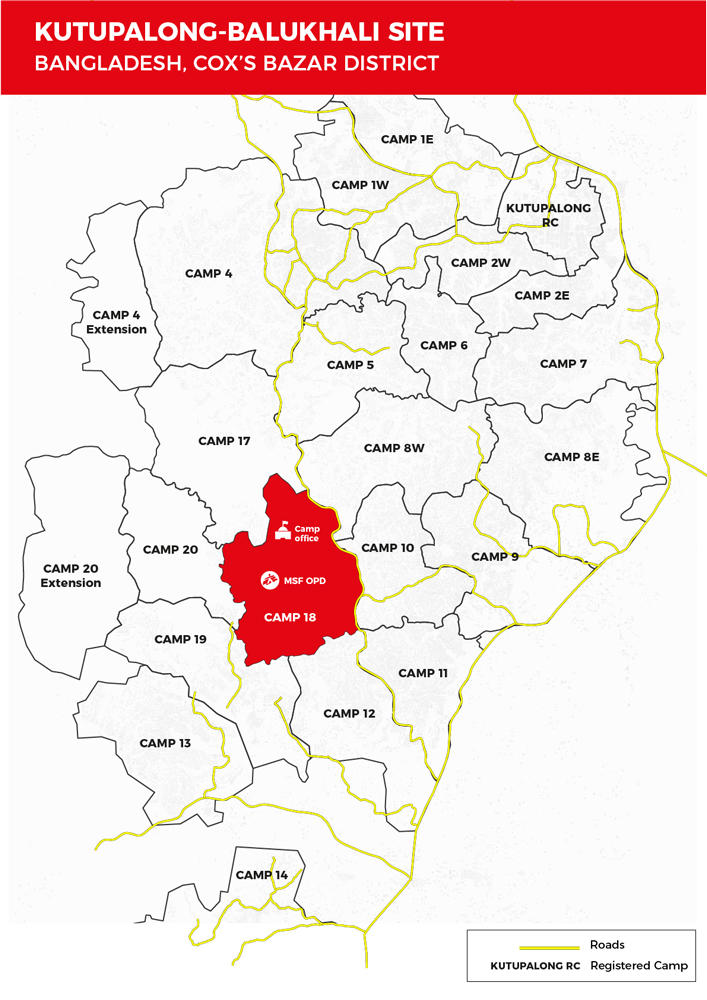

Just as towns are divided into districts, so is gigantic Kutupalong-Balukhali camp in Bangladesh. Still growing, there are now 22 camps. Over 620,000 Rohingya refugees have sought refuge in Kutupalong-Balukhali since fleeing the violence that erupted in Myanmar in August 2017. They have set up shelters on the hillsides of Cox’s Bazar. A road crossing the camp from north to south allows people to move around and facilitates the delivery of aid among seemingly countless hills.

The road leads to Camp 18 situated in the southwest of Kutupalong-Balukhali. All that distinguishes this camp from the others is that it is one of several areas set up to host Rohingya refugees and relieve pressure on over-crowded areas in the east of the camp. Otherwise, with its steep paths winding through rows and rows of tightly packed shelters, it resembles all the other camps. There are more than 29,300 Rohingyas, i.e. some 6,500 families, living in Camp 18 that is now home to heads of families Hasina, Fatima and Mohammed.

Hasina, aged 35

Hasina is a widow. After her husband was killed in Myanmar, she fled with her five children—two boys and three girls.

Hasina arrived in the district of Cox’s Bazar in October. She has relatives living on the same path who give her some help, but every day is a struggle. Firstly, the closest water point isn’t working so she has to go to another area of the camp for water. Then, she needs firewood to cook food but her children are young and she’s scared to send them into the forest to forage for wood. There are no trees left in the vicinity and it can take up to three hours on foot before finding any. A few Rohingyas in other of the camps have struck lucky because they’ve been given small gas stoves.

The onset of the monsoon means even more problems for Hasina. She’s worried her shelter won’t withstand the bad weather that brings torrential rain and strong winds. Like all the others, her shelter is a small, flimsy construction made of bamboo poles stuck in the earth and thin bamboo stalks woven together to make walls. The entire structure is covered with plastic sheeting.

Many refugees put something heavy, usually bags filled with earth, on top of their shelters to stop the sheeting blowing away. All the shelters are constructed in the same way, using bamboo. The Rohingyas make them themselves with what they’re given by aid workers.

Fatima, mother of four children

Fatima Khatun started off in densely populated Camp 16 before being forced to move to Camp 18 in the west. To help her get settled in, she was given a kit with supplies for a shelter and instructions on how to assemble it.

But Fatima is also a widow and couldn’t construct her shelter. So she asked the Maji (the Rohingya leader in charge of the sector of the camp where she lives) for help and he sent some volunteers to give her a hand.

Fatima fled to Bangladesh with her four children, aged 3, 7, 9 and 11, in October. But this isn’t her first time in the country. She had already fled Myanmar in 1992 to avoid the authorities subjecting Rohingyas to forced labour.

She ended up spending two years in a camp in Bangladesh. She then returned to her village, only to find her home had been destroyed. She and her family built a new one but, last year, she was forced to flee Myanmar for a second time. Staying was quite simply not an option.

Another positive aspect for the Rohingya refugees are the camp’s many medical facilities. MSF has opened five hospitals, ten health posts and three health centres providing services round the clock in the various camps. When one of her two sons fell ill, Fatima took him to the MSF clinic in Camp 18 for a consultation. She was told her son had mumps.

Medical treatment, distributions of food and essential items like bed nets and jerry cans, digging wells to supply water… Humanitarian aid comes in all shapes and forms in Kutupalong-Balukhali that is now the world’s biggest refugee camp.

MSF’s clinic in Camp 18

The MSF team give on average 150 medical consultations a day in its clinic in Camp 18. Like everywhere in Kutupalong-Balukhali megacamp, the most common illnesses are diarrhoeas, respiratory and skin infections.

Mohamed, aged 45

While the refugees’ needs are mostly met, distribution of aid can be unequal. Rohingyas able to find casual work manage to do better for themselves. Like Mohamed Eleyas, who’s a daily labourer. This 45-year old father fled Myanmar last year when one of his sons went missing.

Mohamed works periodically, so he’s been able to get a phone and call his brother every now and again. Mohamed was the owner of a grocery store in his village in Myanmar, but he has lost everything. Soldiers burnt down his shop and his home has been reduced to ashes.

His shelter in camp 18 is clearly less comfortable than his home used to be. There’s a kitchen with a clay oven on the earth floor and two rooms, where a prayer mat is the only decoration. But, there’s a water point nearby, which is a real advantage. Rohingya families in some newest camps are not so fortunate, like in the west in the extension to camp 20 where wells and latrines are few and far between.