More women and girls than ever before are currently forcibly displaced — at last count an estimated 32 million worldwide. Some are still on the move.

Preventing maternal death: obstetric care

Burundian refugee Gloria, expecting her third child, struggled to reach Tanzania. Now in Nduta refugee camp, she finally has access to emergency obstetric care.

Pregnant women are a part of all displaced populations, as many women and girls who are forced to seek safety in their own country or beyond are of reproductive age: between 15 and 45 years old.

Lack of access to routine care puts pregnant women and their babies at risk, but lack of emergency care can be life-threatening.

Fleeing when pregnant can increase the risk of miscarriage, or pre-term delivery. Problems that could be otherwise managed—to control anaemia or vaccinate for tetanus, for example—can take on grave proportions.

Evidence shows that a mother’s death also affects the survival of her remaining children.

In Nduta, Tanzania as in other places, the network is as important as the individual sites of care: mobile clinics, health posts, MSF’s maternity hospital and the external Kibondo hospital are all linked to ensure care is available as widely as possible for pregnant women and girls.

Alleviating further suffering: sexual violence care

Jonquil is a midwife on the search and rescue ship operated by SOS Mediteranée with medical support from Médecins Sans Frontières. Not everyone survives the crossing. For those that do, their time onboard may be the first time they receive healthcare.

Wherever MSF meets displaced women and girls, some will be carrying pregnancies due to rape. Testimonies of rape and other forms of sexual violence are common in the dedicated “women’s shelter” on the MV Aquarius.

In 2017, close to two out of three of the women and girls on board were single travellers—another very vulnerable group in the displacement context. Two in five of those were from Nigeria, and reports assert many are being trafficked for the sex trade in Europe. Nigerians rescued on this dangerous crossing are now more often female than male.

MSF’s two or three-day encounter on the ship with these young women is a brief but valuable opportunity to alert them to the risks they might face and provide them advice about assistance such as protection onshore.

Ruksana, a midwife, has been working in Kutupalong, Bangladesh for six years. In August 2017, her clinic started to see a sharp increase in patients having suffered sexual violence among the new influx of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

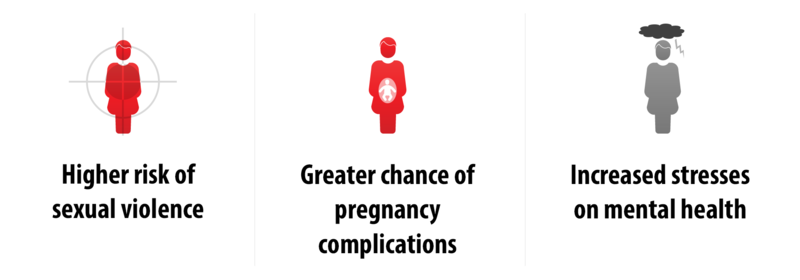

Sexual violence can be opportunistic, or organised. It can be a reason to flee but also can be experienced at any stage of displacement.

Sexual violence is a medical emergency, requiring treatment within urgent windows of time to prevent unwanted pregnancy or possible infections such as HIV. In many cases, the window for prevention will be closed by the time care is sought.

In spite of this there is still important care that can be offered. Psychological support is essential to aid resilience and recovery. But due to stigma, shame, or being overwhelmed by other needs, victims of violence may not seek care.

Among the most effective ways to reach people who need care is to let them know it is available, to ensure confidentiality, and to integrate it into other health services, with dedicated staff.

Drawing on strength: Mental healthcare

Half of the Syrian population has been forcibly displaced. Salma fled with her children and brother-in-law from outside Damascus in Syria, south to Daraa, then crossed the border into Jordan. After a brief stay in Zaatari refugee camp, she moved to Irbid.

For some displaced women and girls it is possible to find safety, or at least relative safety, compared to where they have left. But this may be juxtaposed with the legacy of violence, and multiple pressures due to the new environment. On top of this, women will often prioritise the needs of their family before their own.

In Jordan, for example, many Syrian women need to draw on all their inner resources to shoulder complex responsibilities. They may be struggling to support their family financially or, having lost their husband, to support them as the sole parent. Typically it is their children’s suffering that brings them to a clinic like MSF’s.

In Jordan MSF provides mental healthcare to children and their mothers in Irbid and Mafraq. An all-female counselling team shares tools to help women understand what’s going on and respond in an effective way. Equipped with a new sense of strength, displaced women and their families can start seeking to thrive instead of just survive.

Following their footsteps

As global displacement has increased in recent years, so too the numbers of women and girls on the move, whether internally displaced people, migrants, asylum seekers or refugees. Their journeys have also diversified and lengthened in the face of each new obstacle to safety. They do not need our judgement; they need a range of supports that can meet them on the way.

Women and girls in particular need extra medical and psychological care, and protection. For many, these needs will often overlap. Their health and wellbeing can suffer severely if healthcare is denied—as it will be at many critical points of their journey.

Although many displaced women remain invisible, MSF is following their footsteps where possible to provide medical care. We are also equipping the women we meet with knowledge and tools to make choices in managing their health, as their uncertain journey continues.