They survived enslavement, kidnapping, persecution, poverty and in some cases, sexual abuse. To them, the only light on the horizon lay just beyond the Mediterranean.

They knew the journey would be long and perhaps even deadly. Still, they decided to risk it all at sea— some for the sake of their children, others for a chance of their own at a future.

Many did not know how to swim, and not a single one had a seaworthy lifejacket. And when their Libyan smuggler pushed them onto a severely overcrowded boat under cover of night, all they could do was hope they would make it.

Now, on board the Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) rescue vessel Dignity I, the survivors can breathe their first sigh of relief and share their testimonies, as they eagerly await a new life in Europe.

Here are their stories.

paTIent story: desperate measures

“Our smuggler told us it would take four to five hours to reach Italy," says Abu Omar, a 41-year-old Sudanese father of four young children. "I knew he was lying. But when a man is desperate, he is willing to believe anything as long as it gives him hope.” He was overjoyed that his family had made it this far.

Next to him, his wife Maha cradles their six-month-old baby.

Abu Omar calls "lawless" Libya, where he was born and raised, “the most dangerous country in Africa."

"Ever since the war came, life has been unbearable," he says. "There is killing and theft everywhere. My brother Tamer, who is 25, was shot in the leg because he refused to hand over his car to thieves.”

His brother is also among the 122 people rescued in October from an inflatable boat. The vessel should never have carried more than 12 passengers.

Because adequate healthcare is extremely difficult to find in Libya, he is now barely able to move around without help, even with crutches, because the operation he had after the shooting simply wasn’t up to standard.

paTIent story: kIdnapped

Others were forced to flee far worse experiences.

A man our team nicknamed Mr A climbed on board the Dignity I with nothing at all — not even clothes. He had thrown everything off because a mixture of fuel and saltwater was irritating the horrific scars zigzagged across his back.

In Libya, Mr. A had been kidnapped and tortured for 10 days. This Malian was just 18 years old, and yet with his slumped back, he appeared a broken man.

"I was taken to a farm where I was beaten and whipped for 10 days.”

“I arrived in Libya eight months ago," he says. "I tried to make a life for myself there but in September, I was kidnapped near Tripoli. I was taken to a farm where I was beaten and whipped for 10 days.”

He speaks in a hushed voice, after our nurse treats his scars.

“They never asked for a ransom or anything," he continues. "They let me go, without ever telling me why they had taken me in the first place. I never understood what happened."

It was thanks to his friends that he was able to afford the smuggler’s fee. “When I was released, they all contributed something so they could send me on my way,” he said.

paTIent story: "We had to go"

On the deck, the rescued have their first chance to rest in days — or longer.

Very soon after they are pulled on board, the vast majority fall asleep for a few hours. They need sleep, but also to be treated with dignity and respect.

They are safe now, and even though they only have the hard floor to rest on for the duration of this operation, they doze off like babies.

As they awake, the Dignity I comes to life. Many of the rescued start to get their smiles back, sharing conversation, jokes and even laughter with fellow travellers.

A group of young men from Ivory Coast performs the aptly-named song “Ouvrez les Frontieres” (Open the Borders) by reggae superstar Tiken Jah Fakoly.

But for some, there is no reason to celebrate. I ask myself what kind of hell they must be going through as they look out onto the sparkling blue horizon.

Candy, a 28-year-old mother from Ivory Coast, sits in a beautiful red wrap dress.

She is simply unable to smile.

“I have no feelings now,” she says, cradling her one-year-old baby Dival. “The love of my life — my husband and the father of my son — is still kidnapped in Libya near Zwara. I tried to wait for him. But it just got too dangerous. We had to go.”

Her son wore a white beaded necklace around his neck.

“There is no hope my husband will ever come back," Candy says. "Sadly Dival will never know his father."

paTIent story: drowning

Another woman on board, from Nigeria, cried desperately for two whole days.

This is the entire duration of the voyage from the search and rescue (SAR) zone just beyond the limit of Libyan waters, all the way to the Italian coast.

She had seen her four and five-year-old sons drown, shortly before our crew arrived.

She was unable to rescue them.

There are many more deaths at sea than the world will ever know.

Even when refugees and migrants make it onto the Dignity 1 vessel, there is still a risk of dying.

Joy, a 24-year-old pregnant woman from Nigeria, lost her life on our boat to what is known as dry drowning.

In other words, there was already too much water inside her lungs when she was pulled on board — she did not survive despite the medical team’s best efforts.

Working on the Dignity I, one is confronted with another horrifying reality: that there must be many more deaths at sea than the world will ever know.

Rescue teams often find lifeless bodies at sea; but how many more must there be that are never found at all?

PaTIent story: faTher's love

Abu Ahmad, a 30-year-old from Sudan, knew the risks when he and his heavily pregnant wife Fatima decided to make the journey.

He had been kidnapped in Libya for two weeks, and only released once his family paid a ransom.

“I was afraid my child would grow up in Libya where he would have to become a criminal in order to survive," he says. "We decided to cross the dangerous sea, knowing we would only ever make it if there was a rescue, for our baby’s sake.

"I want him to have a future, and I want him to have papers, not like me in Libya."

Meanwhile his tall, beautiful wife could not help but wince from the pain in her back. Eight months into her pregnancy, she was heavy, and desperate for a good rest.

paTIent story: "No one enters libya and leaves whole"

Pierre, a 16-year-old from Democratic Republic of Congo, made the journey alone.

Despite his young age, he was articulate, and had a talent for solving problems.

During the journey from the SAR zone back to Italy, he intervened in a fight between two groups of young men, helping calm a moment of tension on board.

“Libya is hell for Africans," he says. His old, tattered Juventus t-shirt reminds me he's just a teenager. "No one enters Libya and leaves whole."

"It is better to die trying to get to safety than to rot and die in a Libyan jail."

"Everyone is threatened with torture or killing, arrest or torture, theft or rape."

For two months, Pierre was imprisoned in Libya for having no valid residence documents.

“We are just desperate people," he says. "We climb onto the boat knowing that we probably won’t make it. But whatever happens to us, it’s better than staying in Libya. It is better to die trying to get to safety than to rot and die in a Libyan jail."

paTIent story: a new life

Zeinab, a 25-year-old from Somalia, used the word “purgatory” to describe her journey.

“I have talent," she says. She is a confident young woman, wearing a bright yellow headscarf. "I want to study and get a good job. I don’t just want to be somebody’s wife.

"I want to be in Europe because I hear that women are respected there, not like in Somalia where women aren't given a chance."

She had spent five months on the road before climbing onto the smuggler’s dinghy.

“It felt like five years, not five months,” she says. One of the months - August 2016 - she spent captive in the warehouse of a Libyan kidnapping gang.

“Many of the women with me in the warehouse were raped," she recalls. "This is happening all over Libya."

Zeinab describes a system of abuse that migrants like her are subjected to in the north African nation.

“If you get caught crossing the border into Libya from the south, you’re kidnapped," she explains. "You’re beaten, humiliated and in many cases raped. Then you pay a ransom to be set free.

“As you make your way towards the coast, you may be kidnapped again, this time by militias operating in northern Libya.

"Either you are forgotten, or you die, or you spend another couple of months in captivity before someone takes pity on you and buys your freedom.

“A Libyan family bought me, and I was forced to clean their house in exchange for food and a place to sleep on the floor.

"I was not paid, of course.

“I was lucky, because I was bought by a family. My friend Saadiya was not — she was bought by a single man, who raped her.[[Article-CTA]]

"After two months, the family who paid for my release gave money to the smuggler so that I could make this trip."

Zeinab recalled the dangerous moment when she and scores of others were packed into the dinghy.

None of the passengers were allowed to keep any of their belongings, including their mobile phones — which the smugglers either kept or threw into the water — and their shoes.

All of the migrants we rescue are barefoot.

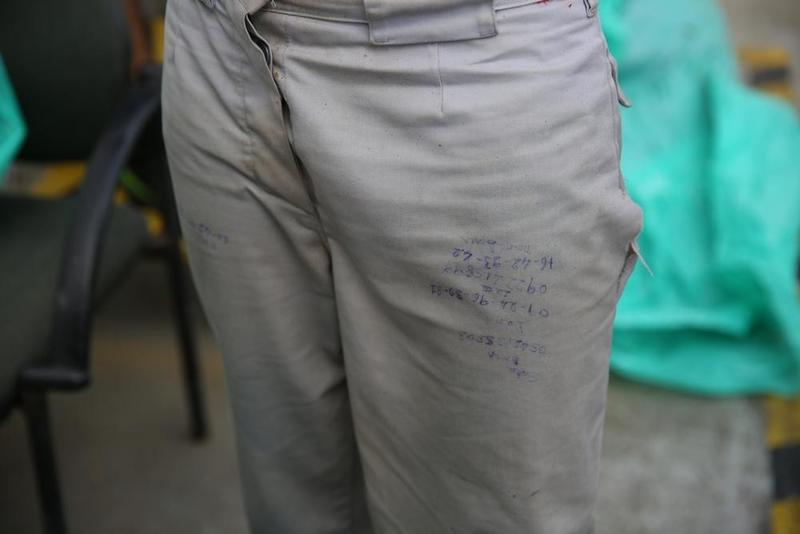

Some have relatives’ phone numbers scrawled on their clothes, so that they can phone them once they are in Italy.

“We set sail on the dinghy without knowing where we were going," says Zeinab. "It felt like purgatory.

“And now, here I am, born again, on this boat, starting a new life.”

MSF on the Mediterranean

In 2016, MSF had three search and rescue vessels in the Mediterranean Sea: Diginity I, Bourbon Argos and Aquarius (the last in partnership with SOS Mediterranee).

Since the beginning of operations in April until the end of November, these three ships rescued 19,708 people. This is about one in nine that tried to reach Europe crossing the central Mediterranean route from Libya.

In the Mediterranean more than 4,690 men, women and children have died so far this year. This is the highest death toll since data is recorded.

fInd out more about our search and rescue operations on the mediterranean sea